- Home

- Stuart Hopps

The Rainbow Conspiracy Page 3

The Rainbow Conspiracy Read online

Page 3

‘There’s a bottle of whisky on the dressing table,’ Clive yelled out from the bathroom. ‘I wouldn’t mind one myself,’ he said, thinking that it might help steady his nerves.

‘That’s a great idea,’ Dennis shouted back, then after a moment he arrived with a glass of whisky in his hand and pulled the shower curtain gently to one side. ‘Here, this should warm you up.’

Clive laughed as the water streamed down into the glass.

‘Better drink it quickly before you drown it,’ Dennis advised.

‘Where’s yours?’

‘I couldn’t find another glass.’

‘It’s over there by the washbasin.’

With such vivid memories of that first encounter flashing past him, Clive sat up in bed and was now wide awake. He could visualise Dennis letting go of the shower curtain and walking away. However he also remembered how aroused he had become, and, on reflection, he wondered whether it would have been better to have taken a cold shower instead, to cool his ardour. Dennis, on the other hand, appeared not to be in the slightest bit interested, removed the extra glass, went back into the bedroom and poured himself a Scotch.

‘I feel a lot better for that. It’s your turn now.’ And Clive handed Dennis a spare towel as he breezed back into the bedroom.

‘No worries, I’ll use this one,’ and Dennis waved his beach towel as he disappeared round the bathroom door.

Clive had tried hard to contain his excitement that day, because in less than twenty-four hours of arriving in Provincetown, he had pulled, and he just couldn’t quite believe his luck. With someone who was almost the embodiment of a gay myth; a nude Adonis who could have walked right out of one of those physical culture magazines he’d always been too uptight to buy. Now fiction was fact and this sexy ex-marine had come back with him to his room, and was now in the bathroom. However, Dennis didn’t seem to want to spend long under the spray, unlike the Englishman for whom a hot shower was still something of a real treat, if not an indulgence.

‘Now I feel all warmed up too,’ said Dennis as he re-entered the bedroom, sat on the only chair in the room and was more than happy to receive a top-up. ‘Say, what are you doing about dinner?’

‘No plans,’ said Clive. ‘I hadn’t thought about it.’

‘Why don’t we have a bite together?’

‘That’s a splendid idea.’

‘Then we can go to Vanessa’s.’

‘What’s Vanessa’s?’

‘It’s a gay bar that’s still open after Labor Day. My girlfriend Marianne knows Vee, the owner, real well. We always go there. You’ll love it.’

‘Is Marianne from Columbus too?’

‘No. I just met her last summer. Marianne has a house out here, but she packs up after Labor Day like most folk in ‘P’-Town, and she went back to New York a few days ago.’

Then Clive remembered how confused he’d been at the time: the chap wasn’t gay after all and this Marianne was his girlfriend. Suddenly the thought entered Clive’s head that Dennis might be bisexual. Clive had never been able to decide whether men like that were simply queer but were unable to come out of the closet completely. Consequently, it had crossed his mind that if that really were to be the case, it meant that the American was in the fortunate position of being able to enjoy the best of both worlds, and that made him appear even more desirable to Clive.

‘Tell me Dennis, why did Marianne buy a house here? Everyone knows that Provincetown’s a well-known gay resort.’

‘She bought it after she divorced her husband. She has a lot of gay friends in ‘P’-Town. They’re a great laugh, and I guess she likes being around them. For that matter, so do I!’

The conversation had now become thoroughly ambiguous and Clive didn’t know where he stood with his ex-marine. He just couldn’t decide whether he was being led up the garden path or whether Marianne was just another fag hag.

‘Look Clive, I need to get back to my rooming house, change into something warmer and pick up some dough.’

‘That’s fine … I don’t feel like eating too early.’

‘Me neither.’

There then followed the first uneasy pause between them since they had met, and Clive wondered whether Dennis was wavering under pressure. On the other hand, he felt the lifeguard was big enough and more than able to extricate himself from what might have become an uncomfortable situation. Clive averted his gaze towards the window, noticed that the light outside had been fading and, realising that they had almost been sitting in the dark, he reached across and switched on the bedside lamp in an attempt to ease the atmosphere.

‘Look Dennis, I’ll understand if you change your mind about dinner. Anyway, I’ll see you on the beach tomorrow.’

‘No worries! I’ll be back .– I’ll see you in an hour.’

Dennis picked up his bag, and as he went to say goodbye, Clive wasn’t at all sure whether he was going to take him in his muscular arms, or shake him by the hand. In fact he did neither, and gently tapped him on the shoulder, swiftly turned and walked out of the veranda door, leaving Clive in a mild state of shock.

It still struck Clive that it had been one of the most exciting encounters he’d had that summer. Such typical understatement: it had been the most exciting.

Nevertheless, there was a possibility that Clive might be dining alone that evening, such was his uncertainty about his new beach buddy. He recalled that this line of thinking led him to take his time and dress slowly for dinner, and, after a while, he made his way to the bar for another Scotch and invited the owner to join him. So. deciding to steer the conversation away from lifeguards and the like, he asked Ned: ‘What other tales do you have to tell me about Herring Cove Beach?’

‘Say, did I mention the Mooncussers?’

‘The what?’ spluttered Clive, almost choking on his drink.

‘The who, actually. It was the name given to the folk who lived here when it was called the Province Land. The Mooncussers used to go out at night carrying lanterns up and down the coastline, in an attempt to lure ships to their doom. Some stupid ship’s captains would think that these lights signified that they had found a safe harbour and then they would steer their boats in that direction, only to flounder and perish on the rocks. These local guys were no amateurs, you know. They were brilliant at stealing floating cargo while watching the ships go down and sink with their crews still on board.’

‘But I still don’t understand why they were called “Mooncussers”.’

‘That’s because whenever there was a full moon, it was bad for business and the Mooncussers could be seen swinging their lanterns to no avail and cursing at the moon as its beams guided the ships away from the rocks.’

‘It sure wasn’t known as Hell Town for nothing!’ Clive laughed.

Then, as he entered the bar, Dennis interrupted Ned’s tale with: ‘It sure as hell wasn’t.’

‘So Dennis is your date! You English may come across as all shy and retiring, but when push comes to shove, you sure do know how to get your act together.’

‘Honestly Ned, I’m only trying to do my bit for Anglo-American relations,’ Clive responded in his poshest English accent.

It was well after nine and Clive was starving, so he was relieved when Dennis declined Ned’s kind offer of a drink. They were thus able to beat a polite but hasty retreat from Reveller’s Den, leaving Ned to think whatever he damn well liked and not be too offended that they had declined his hospitality. Clive remembered that, once outside, he began to take in the local architecture as they made their way along Town Beach towards Macmillan Wharf.

‘I love those turrets you see on top of a lot of the houses along here.’

‘Yes, they’re quite a feature in New England,’ Dennis replied. ‘They’re called “widows’ walks”.’

‘Oh, really! How did they get to be called that?’

‘The story goes that they were built for the wives of the ship’s captains, so that they could get a good view of the s

ea while keeping watch and waiting for their husbands’ boats to return. All too often they didn’t come home and many of the wives were left widowed, and that’s how these lookout turrets got their name.’

‘Well Professor Montrose, you certainly know your local history.’ To which Dennis, sensing that Clive was sending him up, changed the subject and pointed to a restaurant.

‘Say, why don’t we go there. Do you do fish?’

‘I love fish, and it must be good here on the Cape.’

‘It sure as hell is. There’s been fishing on Cape Cod since the American War of Independence. They used to salt the catches and ship them out to Europe.’ Now Dennis was clearly playing Clive along, and enjoying the role of Professor Montrose.

‘So please mister teacher sir, what else can you tell me about the Province Land?’

‘Well, that all depends on whether you allow me to give you an examination later. Of course, I mean in order to test your knowledge of local history.’

‘Please sir, can we eat first? I’m ravenous.’

‘Certainly, my boy. I hoped you’d say that.’

As they tucked into a delicious dish of roast cod and baked potatoes, Dennis refilled their glasses, and continued his history lesson. ‘By 1840, the inhabitants here became rich and very respectable. They exported salt, whale oil and dried and salted fish all round the world and the Town Beach was used as a road, and this became a very busy and prosperous port. Then a most mysterious thing happened.’

‘I say, the plot thickens!’

‘Yes, as a matter of fact, it did. The town records suddenly disappeared without trace.’

‘How extraordinary! But why?’

‘It was suspected, but never proven, that the old families that had become so rich and powerful from the whaling industry wanted to cover up their criminal ancestry. So they conspired to get the town records stolen so that they could never have their respectability challenged. Anyway,’ Dennis’s lesson continued,’by the end of the nineteenth century, the so-called leading families took a slide because the kerosene lamp had been invented; the whalers went out of business and the town became very run down.

‘So when did the faggots start coming here?’

Clive had caught Dennis in the middle of a mouthful and he almost choked on his food. He took a large sip of wine and fixed Clive with his piercing steel-blue eyes. ‘Why did you use that word? Surely you must know how coarse it is. And, besides, aren’t you gay yourself?’

‘Yes of course I am. Aren’t you?’

‘No, Clive … I’m sorry to disappoint you, but I’m not!’

CHAPTER THREE

PAN AM FLIGHT 101 TUESDAY

In Ladbroke Terrace, Clive woke early, he had breakfasted on tea and toast, and was ready and waiting to go with his luggage all packed. Despite several nightcaps before turning in, he had not slept at all well and it showed. Memories of Provincetown had been swirling round in his head, preventing him from having that good night’s sleep he so cherished. Without his habitual eight hours, he could be thrown into a foul temper, which was known to upset him for the rest of the day.

Shirley had become very practised at reading such sleep-deprivation signals, and often, on arriving at the office and having taken stock of the state her boss was in, would make herself scarce after a quick cup of coffee, and leave the rest of the staff to deal with Clive. After all, Spoke Associates had by now assigned a number of artists to her guardianship and her occasional disappearances were consequently a matter of course, although, truth to tell, on a really bad Clive day she was more likely to be found at the hairdressers. Not that her gorgeous auburn locks needed too much help, you understand, although she was in the habit of encouraging her French coiffeur, Olivier, to liven up the colour from time to time.

Clive could go on and on about the problem of lack of sleep to the point of obsession and, such was his self-control, he was even known to drag himself away from an event he was particularly enjoying once the clock had struck one, thus creating his own brand of Cinderella vanishing trick. Mr Spoke maintained that an orderly lifestyle produced healthy results and believed that his youthful forty-year-old appearance was due to self-discipline, exercise and moisturiser, but not necessarily in that order of importance. He also freely admitted that Shirley’s strict attention to his dietary needs, as well as her shopping tactics, ensured that he ate well and regularly, and this, combined with his daily visits to the gym, resulted in his keeping in such very good shape.

The black cab that Shirley had ordered pulled up outside 18 Ladbroke Terrace slightly ahead of time and, as Clive opened his front door to the smiling cabbie, he could smell the fresh spring morning air and noticed that early rain had left a fine patina of glossy moisture on the road surface outside. He was travelling fairly light that day but still couldn’t get everything into one case, so the London taxi driver helped him get his large suitcase up front, into the driver’s area, while Clive boarded the large passenger compartment behind with some hand luggage, and stretched out along the roomy back seat. Hours of travel lay ahead: first to New York, then changing planes at Kennedy Airport for Columbus, Ohio. The traffic out to Heathrow was reasonably light that morning and he was more than confident that he would arrive in good time to catch his plane. Such was not always his experience, since only ten days previously, he’d nearly missed his flight to Los Angeles because of a bottleneck on the Hammersmith flyover.

Lately, he’d got to know the West Coast well and he really enjoyed the laid-back atmosphere he found in California. His frequent LA visits were largely due to Anthony Pollard, one of Spoke Associates’ most cherished clients, who’d become the toast of Hollywood that year following his Oscar-winning performance in The Butler. This had clearly boosted Clive’s own reputation no end and so, once again, that Spoke nose had paid big dividends. This resulted in what some of his colleagues admitted was the beginning of a burgeoning international career for both him and Mr Pollard. In addition to this, recent Broadway seasons had recognised the success of several West End plays, and, due to a healthy reciprocal agreement between British Equity and its American counterpart, it was now quite commonplace for London productions to transfer to New York, and this had proved quite lucrative for Spoke Associates and several of Clive’s clients.

The English had landed.

However, at present, Clive was much more preoccupied with the notion of take-offs. No matter how many flights he’d taken, he still experienced minor panic attacks as his plane raced for levitation and he felt his own life was in the balance. He had to will himself to relax, and lessened the tension in his fingers by forcibly releasing his grip on the armrest of his seat. There was that terrible moment when he seemed to leave his stomach behind him and had to wait for it to return to its rightful place once the aircraft had levelled out and attained the horizontal. It wasn’t until the seat-belt sign had been switched off and the first dry martini was safely in his hand that he felt he could tell himself that, provided there was no turbulence, the worst was over.

As his taxi swung past the Hogarth Roundabout, fears of flying were replaced by thoughts of Dennis and his first visit to Columbus in ‘76. Although it was eight years since they’d last met, Dennis had invited Clive to his home town and even paid for his airfare. He also remembered now that it was on the pretext of Clive meeting Michael Poledri, who had become Dennis’s partner. Then he recalled the time when Dennis had invited him to join a skiing trip to Aspen, but that had been in the spring of ‘79, some three years later. Up till then, there had been almost no communication between them whatsoever, and at the time, Clive had been really surprised to hear from Dennis, who was apparently travelling without Michael.

So it was decided that Clive would join his Columbus buddy in Colorado and, because the pressure of work at Spoke Associates had been building up, Shirley encouraged her boss to take a break. However, she had absolutely no idea that he was meeting up with his Dennis and had just assumed that he had gone on a ski

ing holiday on his own.

Clive remembered that in Aspen he had found Dennis in a rather agitated state. It transpired that his life had got rather out of control of late, and that he had got mixed up with a very fast crowd. After they had finished dinner, Dennis told Clive that there was a very important matter he wanted to discuss with him, but that he didn’t want to spoil their first evening together and said it could wait till the following morning. However, by the next day, the American seemed much more relaxed and when Clive reminded him that he thought he had something pressing to tell him, Dennis laughed the whole thing off, said he was just feeling a little depressed and left it at that. Nevertheless, before Clive flew back to London, Dennis did ask him to promise that should anything untoward happen to him, Clive would always keep an eye out for Michael. Now in retrospect, the thought crossed Clive’s mind that Dennis must have got into some sort of trouble but, at the time, Clive never found out what it might have been. He was sure his chum could not possibly have anticipated that he would develop AIDS, since the health problem didn’t really begin to spread until well into the eighties. At any rate, a promise was a promise and he was determined to keep his to Dennis: in a crisis, he would always be there for either him or Michael.

As his taxi headed out to Heathrow, Clive recalled that his first visit to Columbus had also been in the month of April, only at that time, he was already in the States, visiting his dear friends the Carlsbergs, who lived in New York on West 89th Street. He had known Susan and Martin for years, and like so many New Yorkers, they were great fun to stay with, most generous and very hospitable. The fact that they lived in a very glamorous penthouse on the Upper West Side may also have contributed to how much he relished staying with them. On that occasion, he was flying to Columbus from La Guardia Airport, and although crossing town had been quite straightforward, the moment he reached the Hudson Freeway, he had hit thick traffic all along the East River and his taxi was reduced to a snail’s pace. True, it was the Easter weekend, but according to the yellow cab driver, the hold-up was due to the Jewish holidays. He explained to Clive that thousands of folk were making their way down from Queens and heading out to Long Island in time to celebrate Passover. For the moment, it had slipped Clive’s memory that these two religious events often coincided, but he was even more surprised to learn that the ‘Paschal Feast’, as his driver called it, was what was almost bringing the highway to a complete standstill.

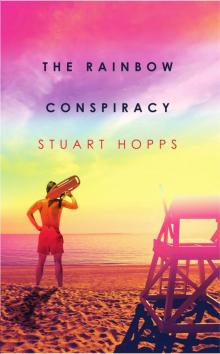

The Rainbow Conspiracy

The Rainbow Conspiracy